Constructing a packaging future that is sustainable

The European regulatory landscape is linking the dots between the European Green Deal, its circular economy plans, waste legislation, and carbon agenda to create a more coherent, clear agenda than ever, it seems. This perception was crystallised by the proposed revision of the EU’s Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive, which was released on November 30, 2022. Additionally, with clear indications of the dangers and commercial potential.

It is evident that businesses must meet demands that are more urgent and concrete than only the ability of packaging to be recycled (which will be governed by stricter standards) and the requirement that plastics contain a minimum amount of recycled material. Another feature, which one would argue the industry has not fully realised, is greater regulatory action in the reuse and refill sectors.

At the Sustainable Packaging Summit in Lisbon in September 2022, Mattia Pellegrini, the head of the DG ENV section at the European Commission, said that obligatory reuse targets would be implemented, perhaps with increasing levels between then and 2040. Reuse goals will be established for primary, secondary, and tertiary packaging, as well as by industry.

Together, these constitute a shift in the environmental standards for consumer-packaged goods in Europe. As the UN Treaty on Plastic Pollution makes progress toward bringing global regulation into harmony, one can look to this as the model for development on a global scale.

How can one remove the obstacles to refilling and reusing? How can the development and expenditure of circular materials be accelerated? How can all stakeholders work together more efficiently to coordinate their efforts and maximise sustainable transformation? In 2023, these issues will be crucial to packaging.

In all the efforts and debates leading up to the following iteration of the Sustainable Packaging Summit, they will also be crucial to the aim of guiding the value chain forward towards a sustainable future for packaging.

Alternatives to packing

The packaging sector has been exploring materials created without the use of fossil fuels.

The industry is investigating the use of non-food crops, like cellulose and seaweed, in order to address the problem of plants for bioplastics conflicting with food production. The development of new technologies also concentrates on non-edible crop byproducts.

The creation of these materials has, up until now, been somewhat small-scale, but in 2022, some encouraging scale-ups and partnerships were witnessed.

Some interesting pitches were heard at the Innovation Horizon conference in Amsterdam, including ones from a start-up using red seaweed and another that was removing natural biopolymers from leftovers from the agricultural sector. The industry is very passionate and motivated, and one can anticipate that in 2023, growth momentum will accelerate.

Start-up Notpla and the packaging manufacturer Coveris collaborated to introduce seaweed-coated carton packs with grease- and water-resistant qualities. This kind of collaboration encourages scaling up; thus, in 2023, further breakthroughs are anticipated.

Trees are crucial in lowering atmospheric CO2 levels. Interesting advances in alternate fibre materials will have occurred in 2022. The partnership between AB InBev and Sustainable Fiber Technologies, which produced secondary packaging for Corona beer using residual barley straw and won the Sustainability Awards 2022, was noteworthy.

Additionally, a Ukrainian start-up called Releaf Paper created a method for converting cellulose fibres produced from dead leaves into paper packaging products in the field of fiber-based packaging. One may anticipate that the technology will advance in 2023 because the company has been granted a €2.5 million grant from the European Commission’s EIC Accelerator 2022 programme.

Package made of paper

While plastics won’t be completely replaced by fiber-based packaging any time soon or at all, one can anticipate that both large and small firms will continue to turn to paper solutions for specific uses. According to what insiders have told, the confectionary and snacking industries may experience some very exciting technological advancements over the course of the upcoming year. Several major companies, including Nestlé, Ritter Sport, and Mars Wrigley, have already launched their own paper-based lines. The paper bottle market will almost certainly continue to grow; Paboco’s solution, which has been tested by businesses like Carlsberg, Coca-Cola, and Absolut, is a prominent example. One can look forward to the release of the bottle’s next generation prototype this year, which will also have a paper closure made by Blue Ocean Closures.

The paper bottle solution from Pulpex and Stora Enso is moving closer to full commercialization in 2023 thanks to a cooperation with Kraft Heinz on a prospective paper-based ketchup container. But there are other innovators in this field as well.

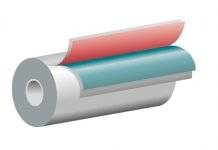

Paper package barrier solutions are also being developed that are more effective and recyclable, and the upcoming year will undoubtedly see more instances in the industry. It’s intriguing to keep an eye on dispersion coatings to substitute polymer-based coated board for paper barriers, with firms like Walki and Kemira leading the charge.

For paper packagers, machinability is a problem in addition to improved material qualities. Given this, one can see the increasing cooperation between packaging manufacturers and machinery manufacturers to make it simpler for businesses to migrate to such new paper solutions without sacrificing quality or price.

Despite advancements, there are still issues and conflicts that the industry needs to solve in the coming year and in the years to come. For instance, will products like the paper bottles listed above genuinely replace plastic on a large scale, or will they continue to be niche products?

Can the innovations currently under development truly tackle the enormous challenge of 100% renewability within the paper waste stream, given that even the most cutting-edge paper solutions still leave some trace of aluminium or plastic layers behind? That needs to be found out.

The EU’s packaging and waste packaging regulations

The long-awaited updates to the EU’s Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive were finally made public in late November 2022. How will the scenarios change throughout 2023, and what do they genuinely represent for our industry?

The Directive, which lays out a number of goals and objectives, is the foundation of the EU’s effort to promote sustainable packaging. It aims to address packaging waste while removing internal market restrictions brought on by member states’ adoption of various packaging design regulations.

The EU wants to go farther to achieve its goals of having all packaging on the EU market be reusable or recyclable in what it calls an economically feasible method by 2030, as seen by the recently announced amendments to the original Directive. The main takeaway is a new goal: a 15% decrease in packaging waste per member state and per person by 2040 compared to 2018. According to the Commission, as compared to alternate routes, this would result in a 37% reduction in overall waste.

The modifications emphasise the complete ban of some formats, the expansion of DRS, and the requirement of recycled content rates.

Additionally, businesses might be required to provide consumers with a specific proportion of their products in recyclable or refillable packaging, but this proportion is thought to be smaller than first thought in light of the industry’s reaction to a leaked version of the proposals.

What does that mean for everyone in 2023? It’s crucial to remember that these changes aren’t yet official or legally enforceable. The suggestions will be presented to the EU Council, the EU Parliament, and all 27 Member States this year in an effort to forge a consensus. They might alter all through this process.

Interactivity and accessibility

Last year, products and broader discussions around packaging design and inclusivity featured inclusive and accessible packaging and interactive design.

Howard Wright, executive creative and strategic director for the UK, Ireland, and Australia at Equator Design, emphasised in a comment piece the need for brands to solicit user feedback and cited colours, lettering, and typeface for people who are vision impaired, dyslexic, or have learning disabilities as examples of the many variations of disability that should be taken into consideration.

The Susie Script typeface, created by Lewis Moberly and Tropic Skincare for dyslexic and neurodiverse consumers, is used on Tropic Skincare’s packaging and website. Coca-Cola UK is the first beverage company to test Navilens technology to assist consumers who are blind or partially sighted. Mimica and UNITED CAPS collaborated to develop a cap for visually impaired and cognitively challenged individuals.

Liz Jackson, a founding member of The Disabled List, stressed that inclusive packaging frequently focuses on mobility and blindness and that disabled people can be wiped clean as a result of things like products not using the word disabled, being too expensive, or not receiving a commercial launch. When creating accessible packaging, businesses must take into account the ways that people with disabilities have “tried to hack their own solutions for years, according to Jackson.

One can only hope that in 2023, there will be additional advancements in this area for a larger range of illnesses and disabilities.

Modern recycling

This year, advanced recycling has received a lot of attention, both in theory and in practice. Across Europe and the US, facilities are being planned and funded; numerous new updates are attributable to Dow and its partners, despite the fact that, according to Ecoprog, over 90 plastic-focused projects were already in the works as of the beginning of 2022.

In 2023, as new plants are being built or have already started, one can anticipate that additional businesses will follow suit. The revisions to the EU’s Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive have drawn criticism because they appear to ignore the downcycling of food-grade waste into non-food applications and the inability of mechanical recycling processes to generate materials that are food-safe by European standards. Manufacturers who care about sustainability may decide to take matters into their own hands to achieve complete circularity for their packaging.

After all, recycling plastics is a worldwide concern, as Dr. Geoff Brighty of Mura Technology emphasised, and in addition to a general decrease in consumption, more efficient recycling techniques are vital. This solution isn’t ideal, he concedes, and as an illustration, Mura is still looking for a way to recycle the processed gas that is used to power the low-pressure boiler of its HydroPRS system. However, there is no denying the industry’s present interest in chemical solutions.

Such processes’ quick scalability will probably pave the way for additional discussions concerning their long-term viability. Their genuine benefits have already been questioned in papers, reports, and life cycle assessments (LCAs). The WWF, for example, worries that they might increase carbon emissions, pose risks to human health, and provide little more benefit than their mechanical equivalents.

More recycling facilities will produce more data with which to address these issues. But unless they are shown to be justified, advanced recycling will probably continue to grow for the foreseeable future.